October 30, 2020 - Great Plains, Oil Museum & Salt Mine

|

| Before we left Wichita, we stopped at the Great Plains Nature Center. I was interested in learning about the Great Plains and the prairie. It must have been something back in the day to see vast rolling hills of tall prairie grass stretching for as far as the eye could see. |

| |

|

|

|

The Nature Center had a small but excellent museum. You wouldn't think they would have mountain lions on the Great Plains but apparently they do.

|

| |

|

|

|

There were three types of Prairie grass: Shortgrass -- seldom growing more than 1 foot in height -- which grew on the western side of the Great Plains. Mixed grass -- anywhere between 1-8 feet in height -- grew in the center of the Great Plains. And Tallgrass -- which could grow as tall as 9 feet -- grew on the eastern edge of the Great Plains. Tallgrass could be four kinds: big bluestem, little bluestem, Indiangrass and switchgrass.

The Tallgrass are as extensive underground as above ground, with root systems reaching a depth of 9 feet. Big bluestem could withstand long droughts as well as prairie fires.

|

| |

|

|

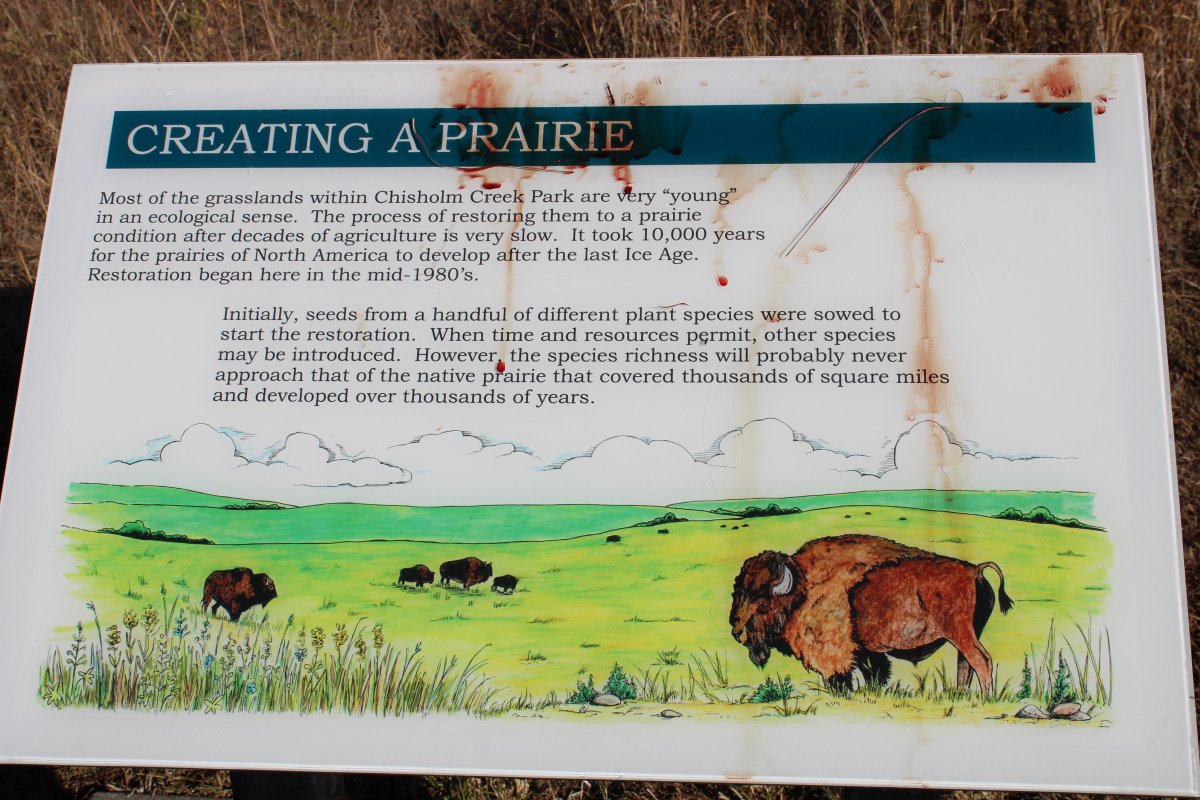

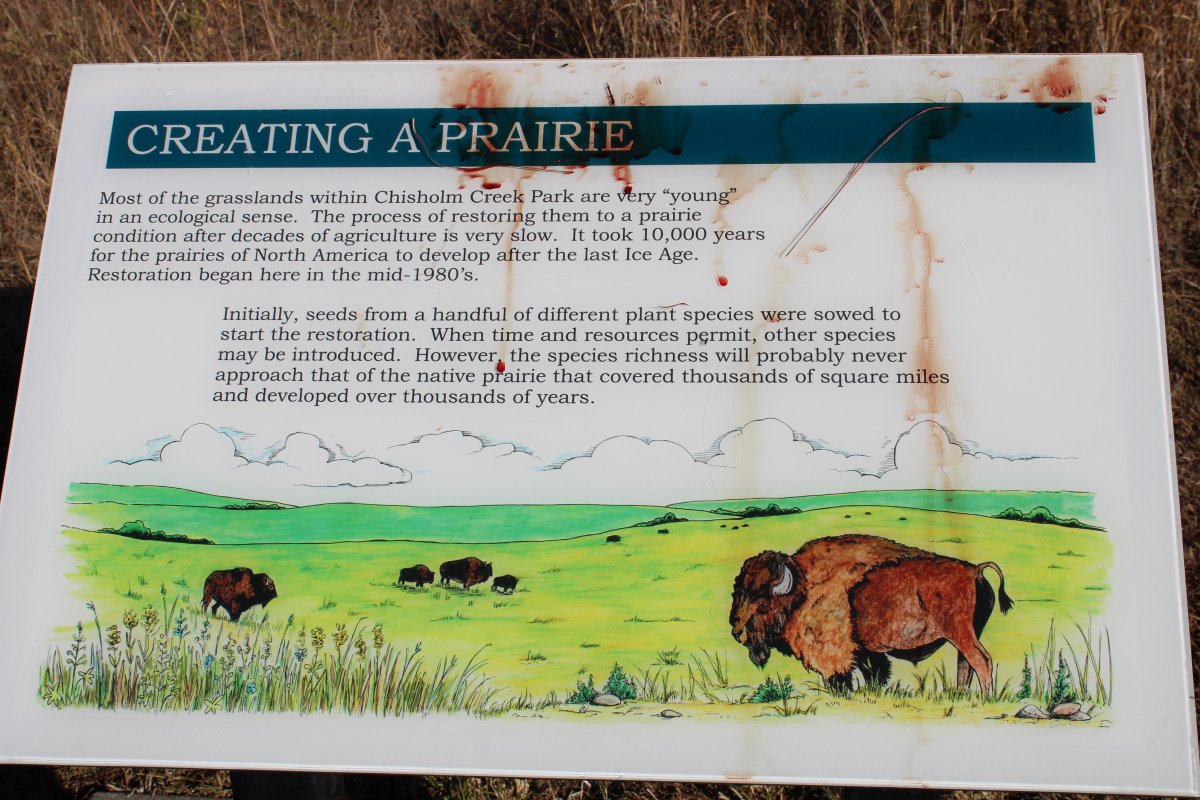

After touring the museum, we went on a hike trail through the Chisholm Creek Park. Jesse Chisholm was the first frontier trader to reside on the present site of Witchita. His trading post, established in 1860, was just five miles from here. The famous Chisholm Trail -- used to bring cattle from Texas to railroad yards in Abilene and Wichita for transport to markets back east -- was named after him. |

| |

|

|

| They are trying to restore Prairie grass here. |

| |

|

|

| It takes awhile though. |

| |

|

|

| Because rich and thick topsoil made the land well suited for agricultural use, only 1% of tallgrass prairie remains in the U.S. today. |

| |

|

|

|

Next we backtracked west to the Kansas Oil Museum in El Dorado, Kansas.

Here Lynnette stands next to one of the last wood and steel derricks which once dotted the surrounding countryside. In was built in the 1940s and is about 100 feet high.

|

| |

|

|

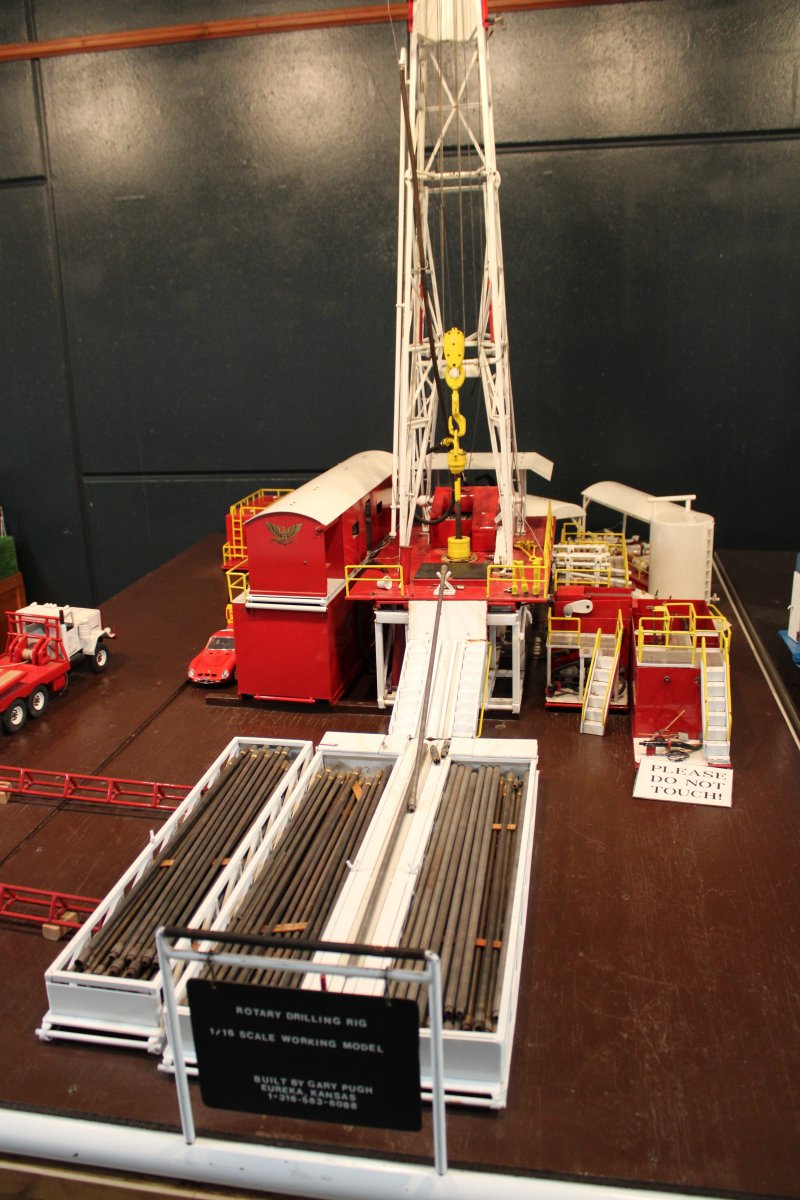

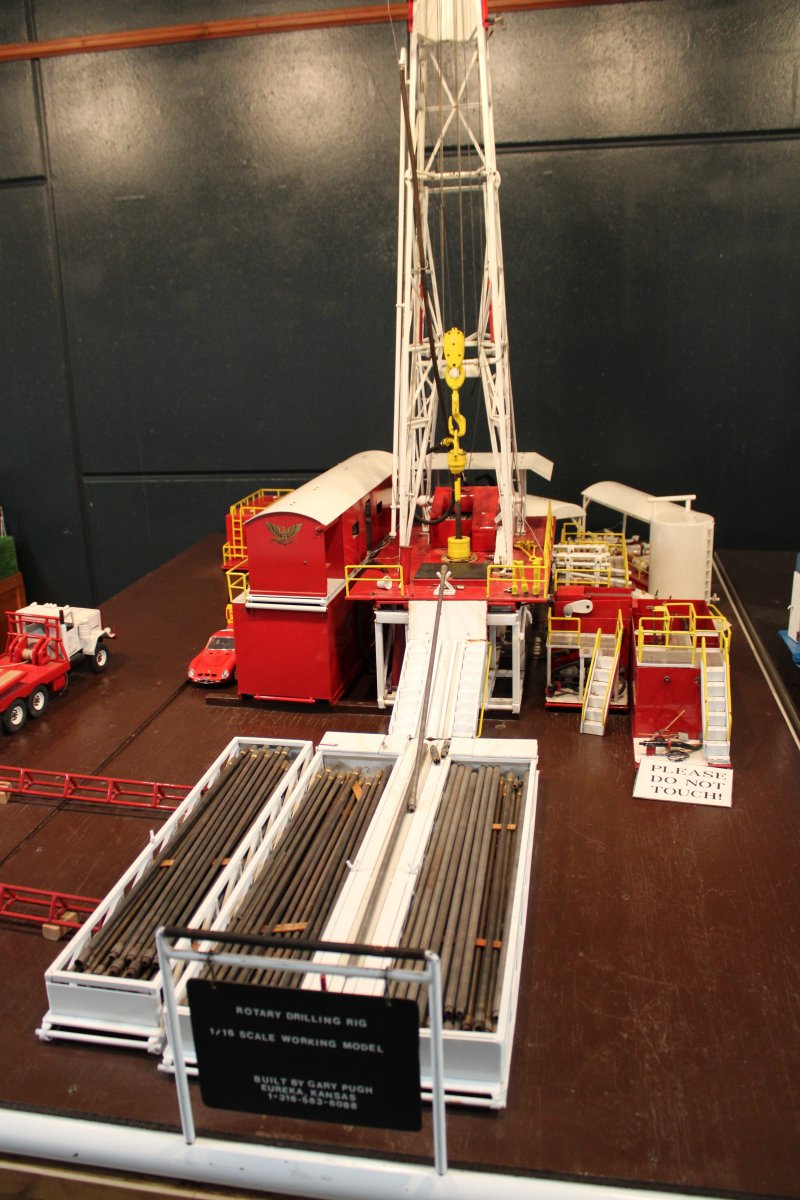

| A rotary drilling rig. |

| |

|

|

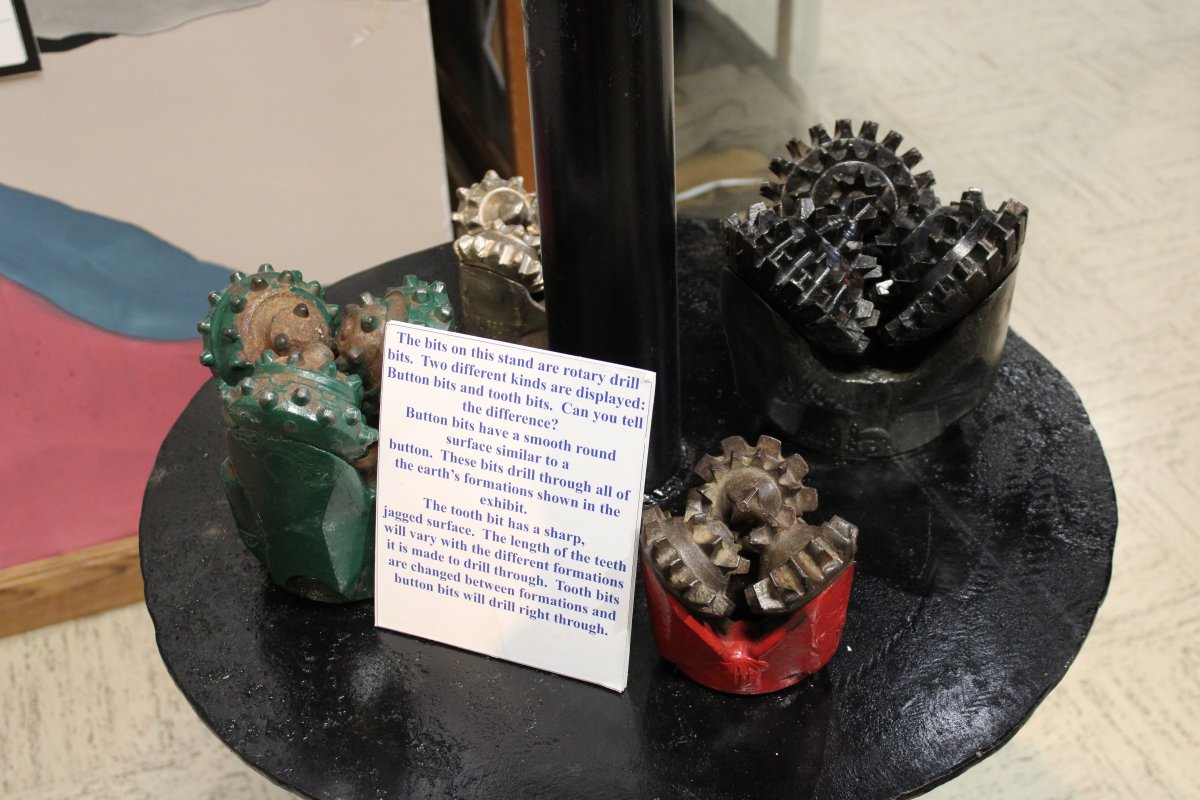

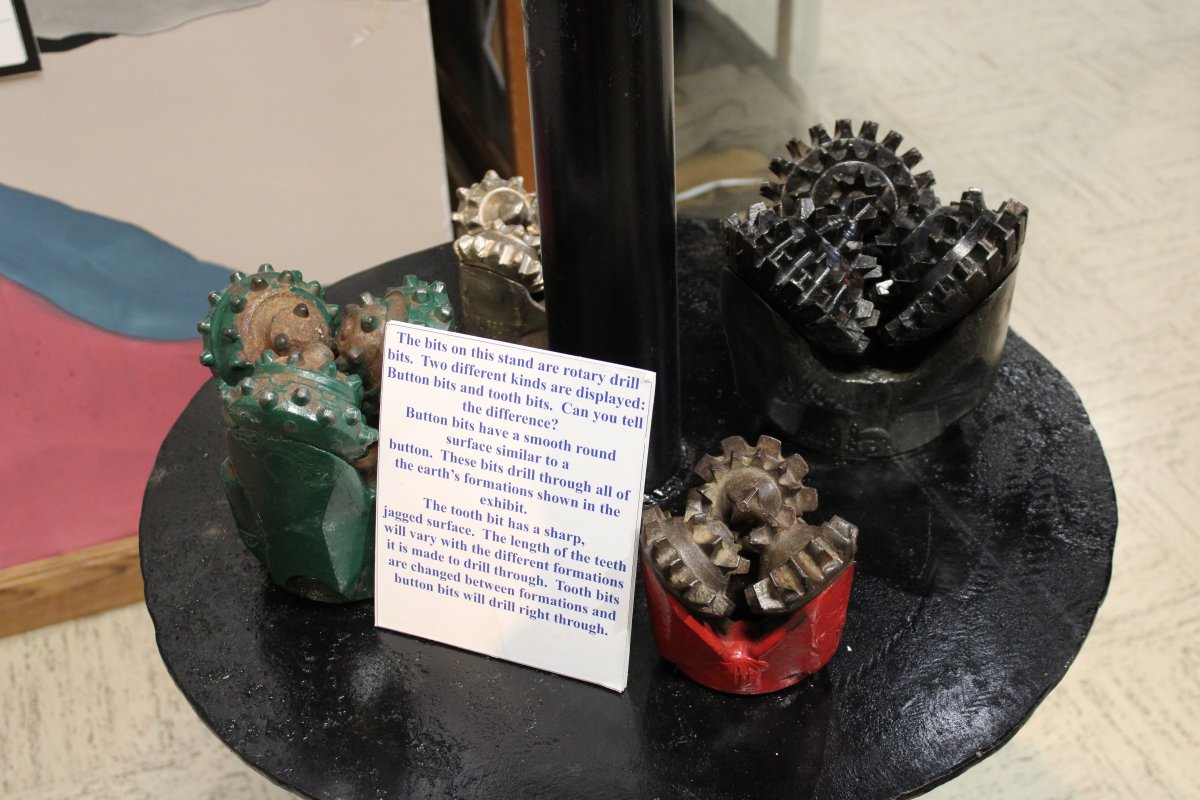

| Examples of rotary drill bits. You wouldn't want to get your hand caught in there while those things were whirring about. |

| |

|

|

|

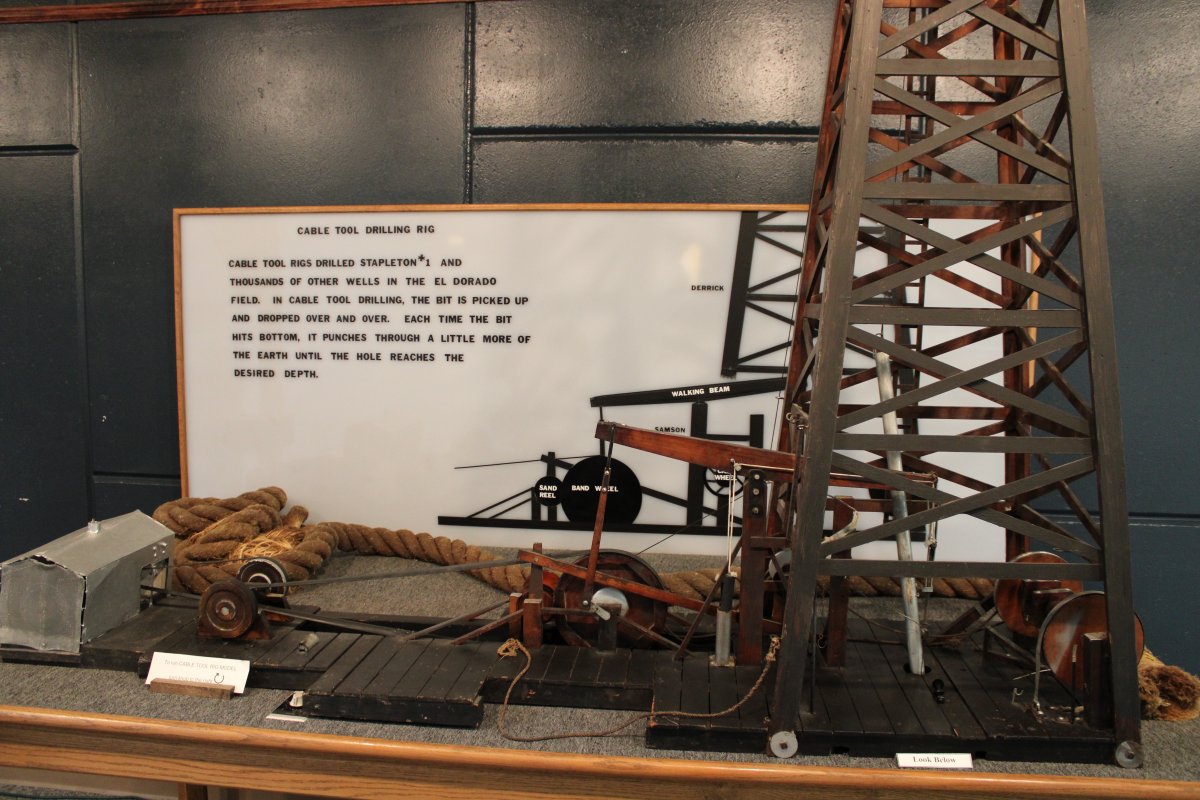

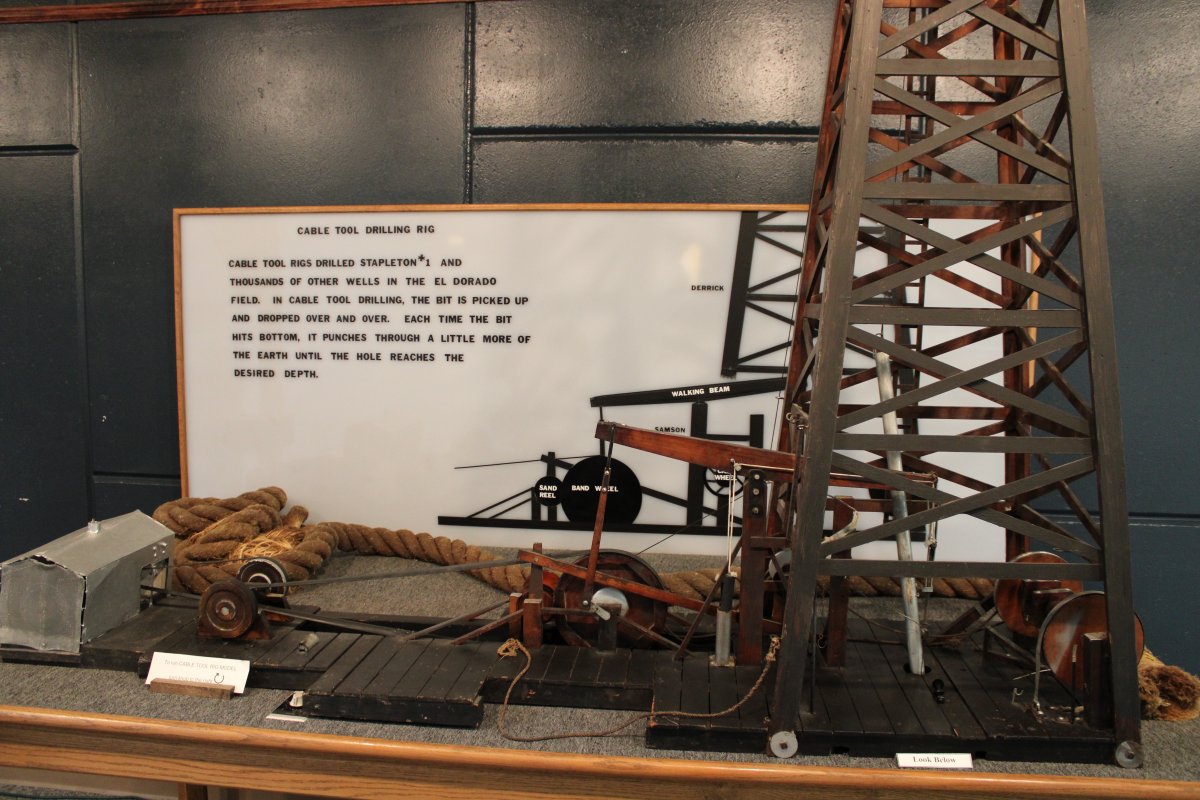

A Cable Tool drilling rig. In cable tool drilling, the bit is picked up and dropped over and over.

|

| |

|

|

| Hook'em horns! |

| |

|

|

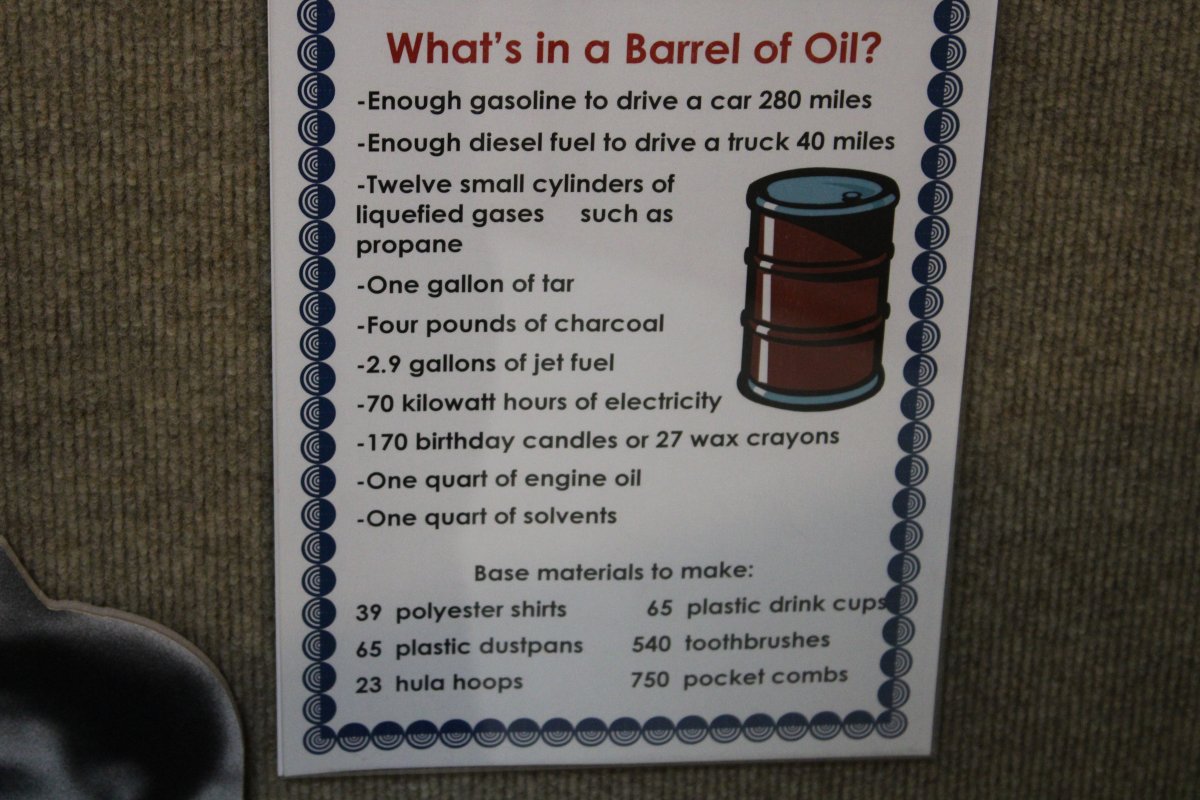

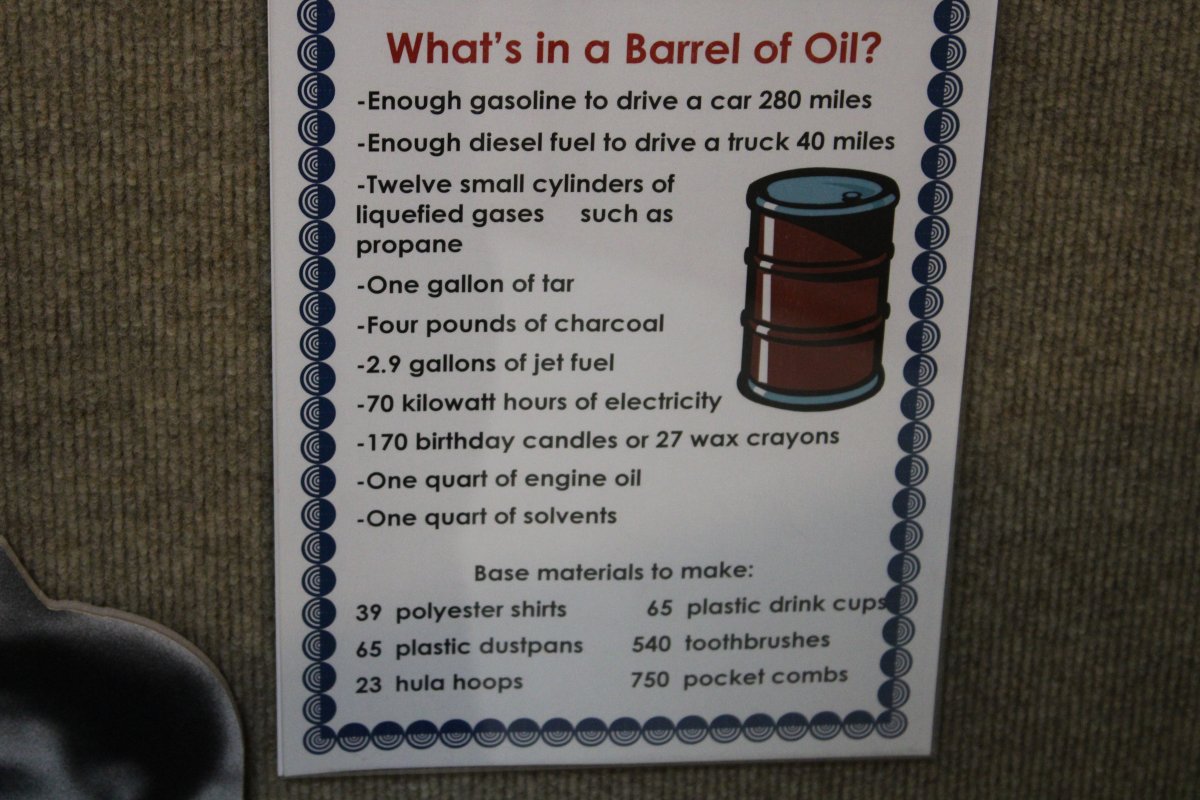

| First, oil was used for illumination in the last half of the 19th century. About the time electricity replaced oil as the source of illumination, the internal combustion engine arrived, and demand for oil for automobiles and airplanes took off. If you think about it, oil is resonsponsible for the quality of life we enjoy today. |

| |

|

|

|

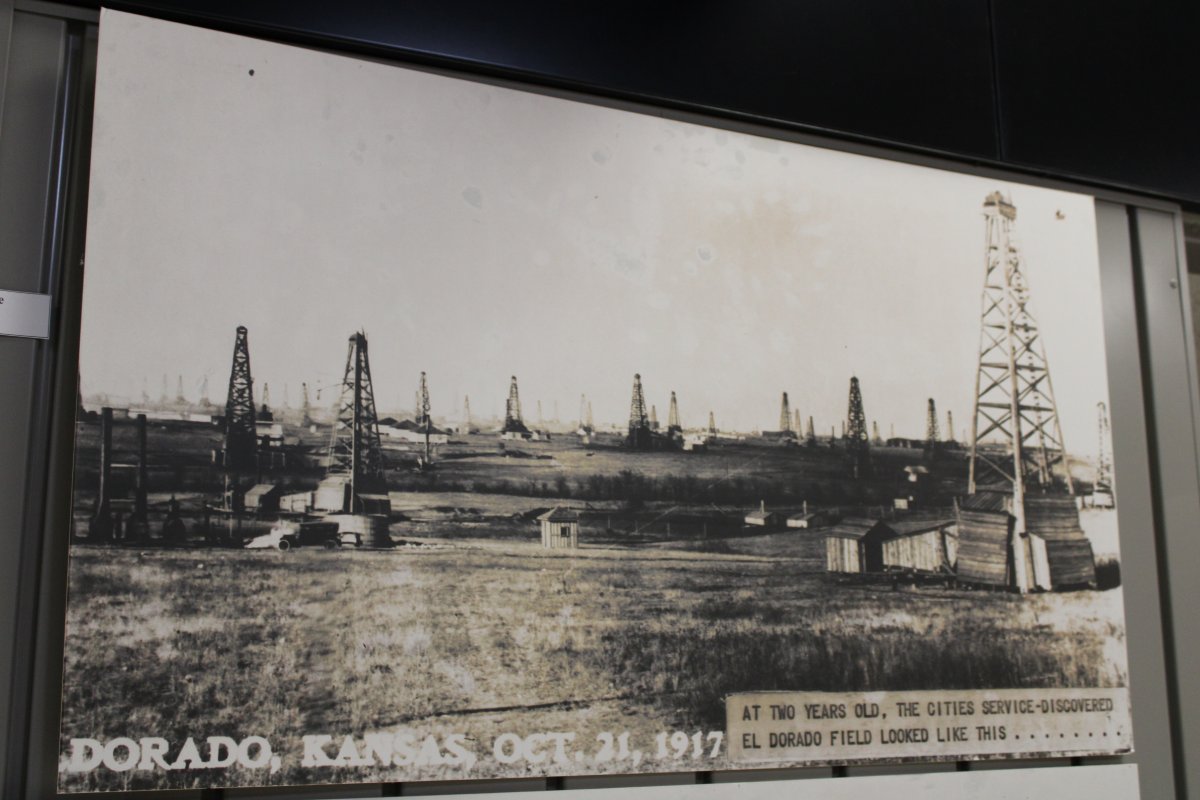

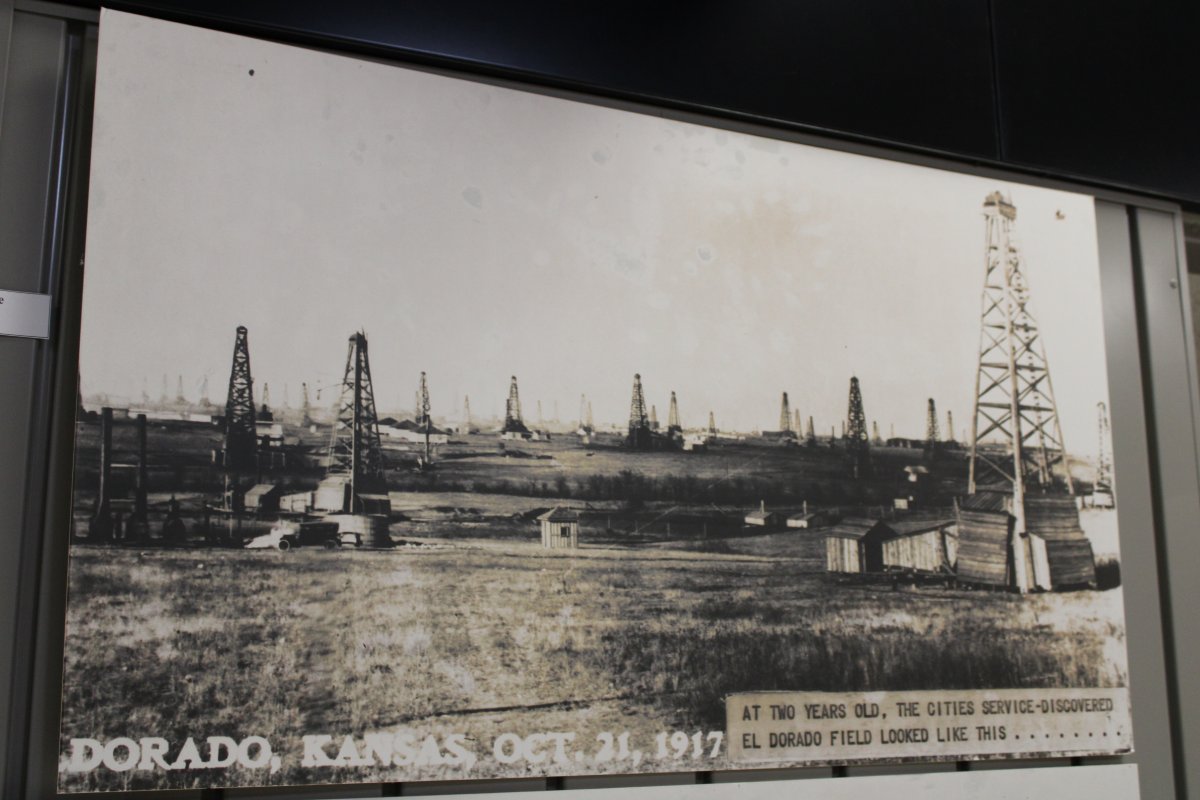

Kansas, I was surprised to learn, actually has an oil history. Prior to 1915, El Dorado was a small, quiet town serving a farming community like most in Kansas. In 1915, the El Dorado Oil Field was discovered; the first oil field found using science/geologic mapping. It was part of the Mid-Continent oil province which encompasses multiple states. By 1918, the El Dorado Oil Field was the largest single field producer in the United States, and was responsible for 12.8% of national oil production and 9% of the world production. It was deemed by some as "the oil field that won World War I".

Two years after the first discovery, the area to the west of El Dorado looked like this.

|

| |

|

|

|

On October 5, 1915, a well east of Wichita launched a drilling boom. The October 5 discovery well revealed the 34-square-mile El Dorado oilfield in central Kansas. The Stapleton No. 1 well produced 95 barrels a day from 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Other wells soon followed east of Wichita. The population of El Dorado grew to 7,000, seven times its size a year and a half earlier. Then it grew to 20,000 people within five years.With the influx of thousands of workers, even Wichita accommodations were overwhelmed. Butler County’s population, about was 23,000 in 1910, nearly doubled in 1920. To house its workers, Empire Gas & Fuel Company (formerly Wichita Natural Gas) built a 64-acre town northwest of El Dorado called Oil Hill. Although Oil Hill and its more than 8,000 residents, swimming pool, tennis courts and small golf course would disappear by the late 1950s, at the time it was called the largest “company town” in the world. The Kansas oil fields petered out in the 1930s or so. The Stapleton No. 1 well, which produced oil until 1967, today is visited by tourists – as is the Kansas Oil Museum, which includes 20 acres of rig displays, equipment exhibits and models of the region’s refinery history.

Here is a tool rack which holds various cable tool bits such as fishing tools, jars, rope sockets and elevators -- whatever those are.

|

| |

|

|

|

From an article written in 2012: "The Mississippi Lime formation in Kansas is the latest ground zero in a gold-rush-style oil boom sweeping the U.S. New technology is turning lands once thought to be sucked dry of oil and gas into vast untapped reserves that could produce for more than 100 years. From Pennsylvania and North Dakota to Texas, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing are quickly turning the U.S. into an oil superpower. By some estimates, 2 trillion barrels of oil are waiting to be drilled -- nearly twice the reserves in the Middle East and North Africa. The newer techniques can produce as much as 10 times more oil than a traditional well. Horizontal drilling works by digging 5,000 feet into the earth, then a mile across in several directions. Using hydraulic fracturing, also known as "fracking," crews then blast sand, water and chemicals into the rock to draw out even more oil and gas. Because of these new processes, Goldman Sachs predicts that in just five years, the U.S. could pass Saudi Arabia and Russia as the world's largest oil producer. Finally, a decades-old dream, talked about by every U.S. president since Richard Nixon, seems possible -- energy independence. And in Kansas that independence will come with enormous prosperity -- thousands of jobs will pay $50,000 annually, tax monies will flood state and local governments and landowners will receive huge payouts -- first through leasing agreements, then if oil is discovered, through hefty royalty checks.

Signs from the many American oil companies in the 19th century. Many are descendants from the original Standard Oil Company which was broken up by the U.S. Government.

|

| |

|

|

|

By 1917 there were 5 refineries operating in Wichita. Seven more were built in the 1920s. But only 3 were still operating at the end of that decade. The Coastal-Derby refinery was the last to close in 1993 with none remaining thru 2010.

Here is an electrically-driven pumping unit used by Chevon to pump a well south of Wichita. The pump could pump wells up to 3,200 feet deep, and produce 130 barrerls per day. This type is still used today.

|

| |

|

|

| This railroad tank car was built in 1929 and used to haul crude oil to the refinery. It could hold up to 9,913 gallons. |

| |

|

|

|

The museum had some houses representative of the ones at the "Oil Town" company town.

Here is a gasolene-powered washing machine!

|

| |

|

|

|

Two electric washing machines.

|

| |

|

|

|

Leaving the Oil Museum, we headed west to a Salt Mine. Lynnette noticed near the Salt Mine was an airport that had an on-field restaurant. So we had lunch at the Hutchinson Regional Airport. As you can see, it is a towered airport.

|

| |

|

|

| This must be the place! We enjoyed a nice sit-down lunch at the Airport Steak House. |

| |

|

|

| An aerial picture of Hutchinson Regional Airport (KHUT) which has three runways. |

| |

|

|

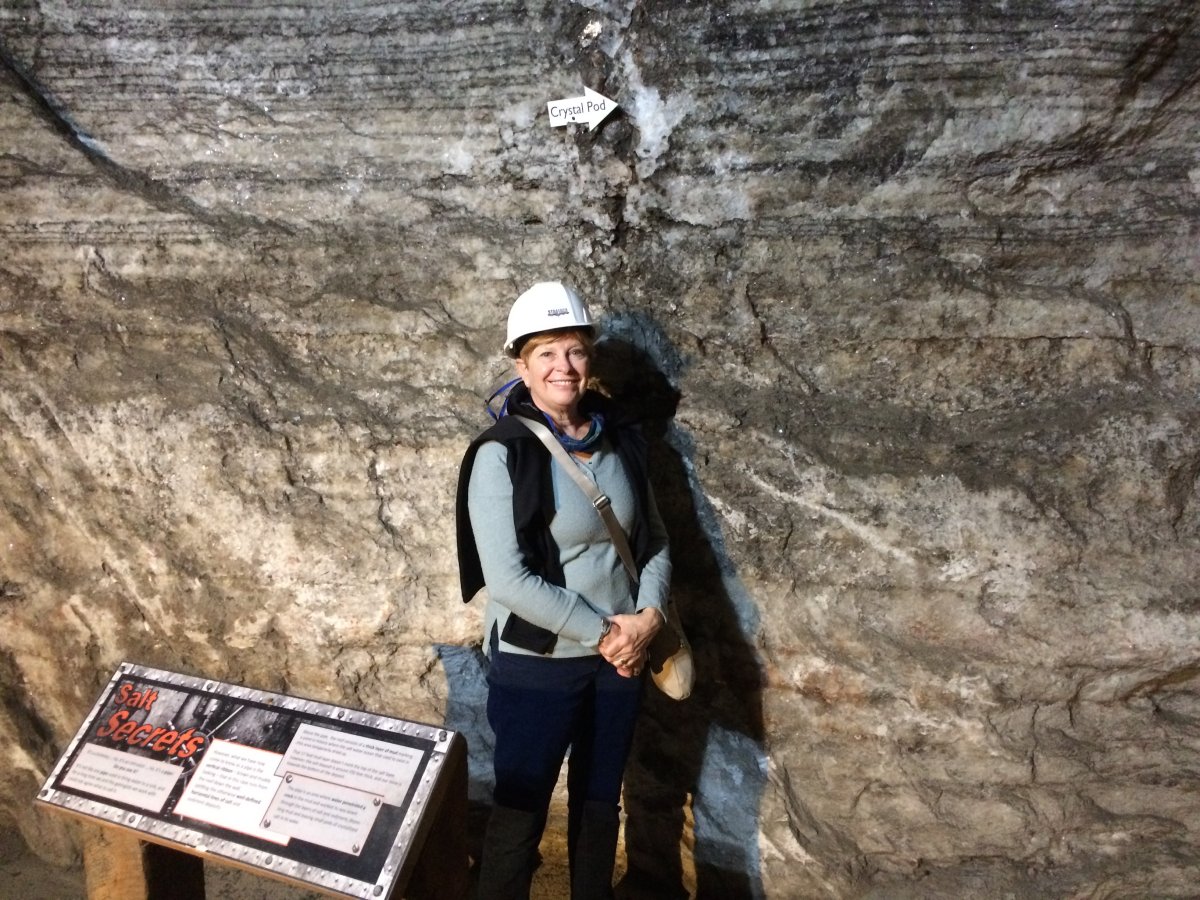

| And here we are at the Strataca Salt Mine underground Museum! |

| |

|

|

|

There is only one way down (and one way back up): by this elevator. All the workers, the tourists, the product (salt), and all the equipment down down below go via this elevator.

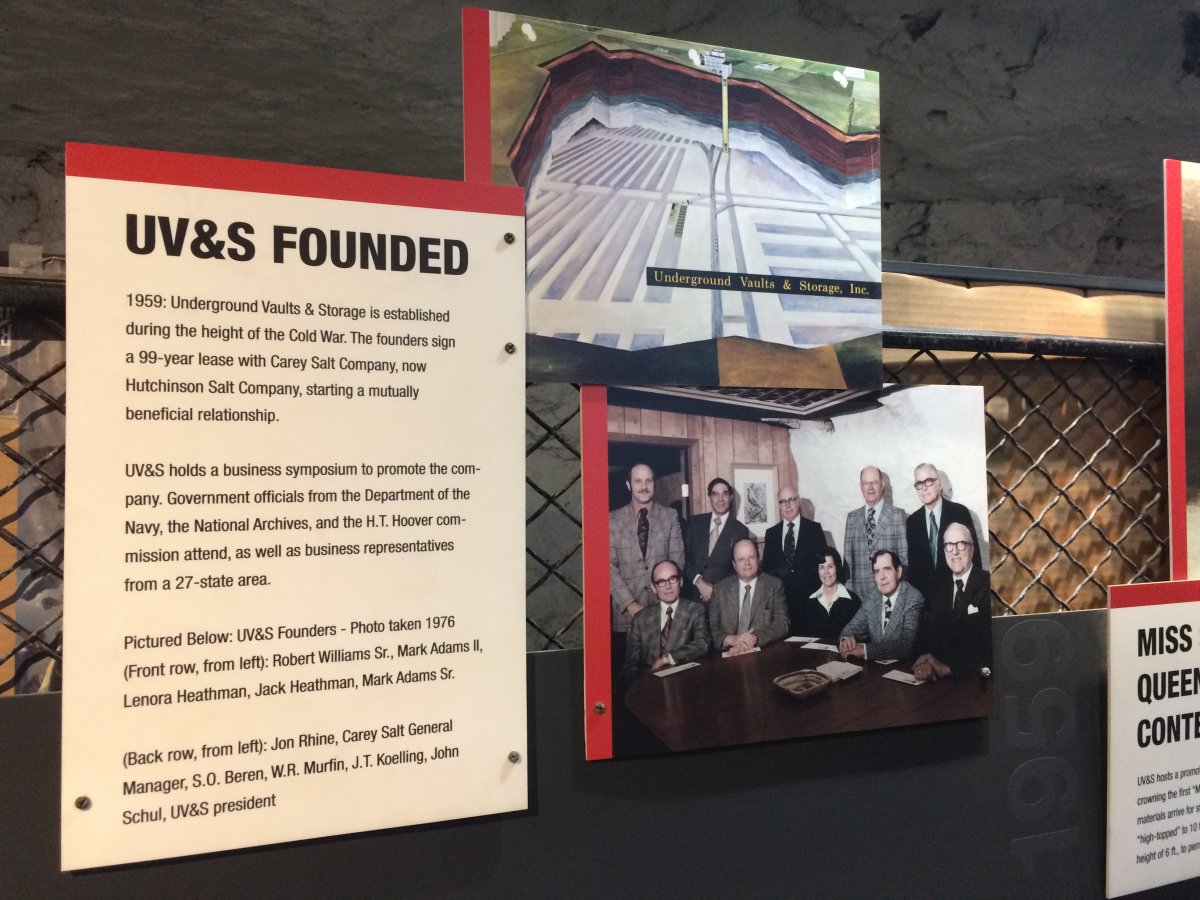

The visionaries of the salt museum knew a project could not get underway without construction of a new shaft. In cooperation with Underground Vaults & Storage, the storage company located in the mine, the two entities agreed to share the cost of the shaft, making the Kansas Underground Salt Museum a viable reality. The shaft had to be drilled through one of the world's largest aquifers. The Ogallala Aquifer covers around 174,000 square miles in eight states and can be as deep as 1,000 feet. In this area, it is known as the Equus Beds and is about 130 feet thick at the site of the museum. For efficient construction without water seepage, the aquifer was frozen. That allowed miners to dig through the aquifer and encase the shaft in concrete. Shaft construction was handled by Thyssen Mining Company, a Canadian contractor. The project got underway March 8, 2004, and took just a day shy of one year to complete. Thyssen utilized the expertise of Moretrench American Corporation for the ground freezing. The process required the sinking of 24 separate pipes to a depth of 150 feet. A liquid nitrogen and salt brine solution pumped into the pipes brought the temperature down to freeze the aquifer. Once the frozen condition was accomplished, excavation began using a crane and bucket methods. The mining cycle consisted of drilling in six-to eight-foot increments, loading the area with explosives, blasting, then “mucking out” (removing) the blasted material from the shaft. The miners would then advance 15 feet and pour the shaft's concrete liner. This action was performed with every 15-foot advancement. On December 22, 2004, the shaft sinking was completed. Finish work on the shaft continued until March 7, 2005.

|

| |

|

|

|

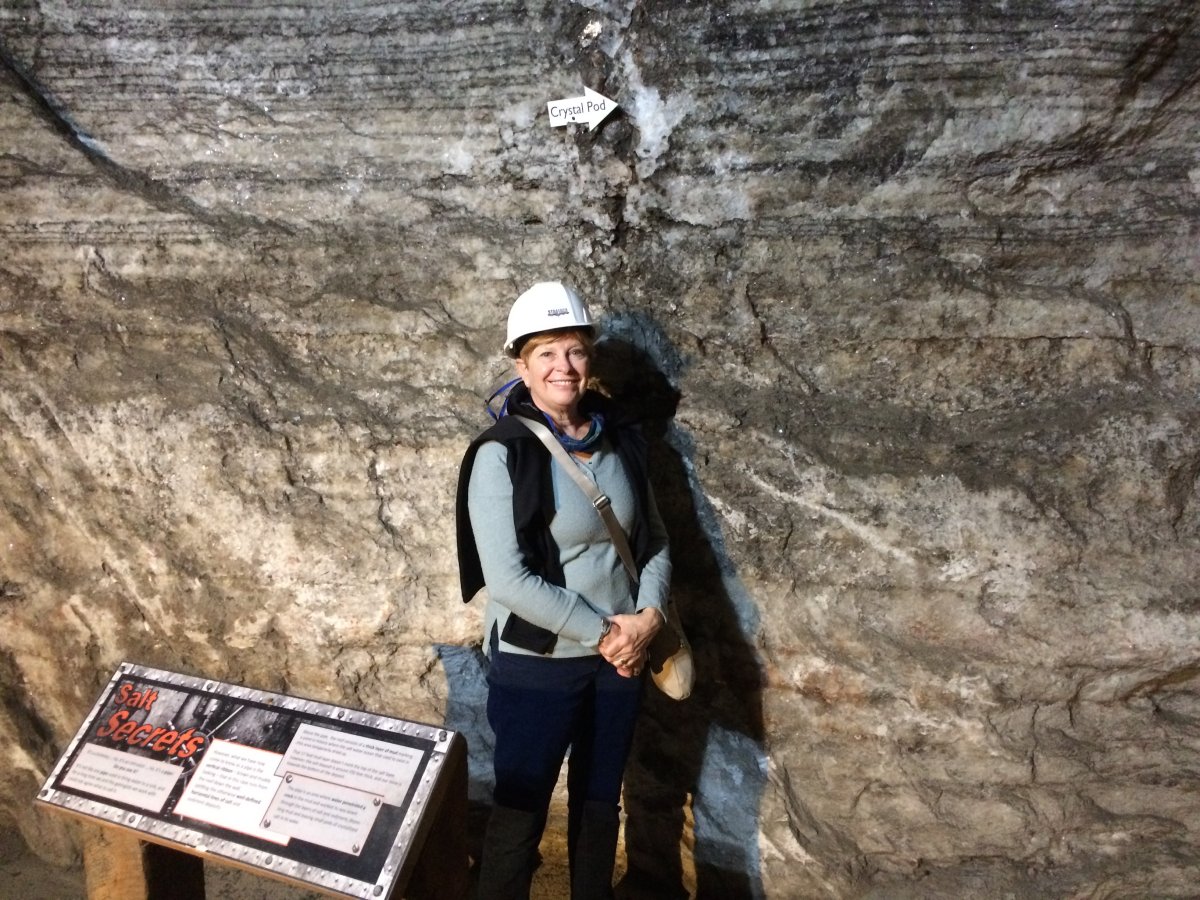

A few minutes later, here we are, 650 feet below ground. The Strataca is a museum is located in the Hutchinson Salt Company mine.

"Salt is the only rock directly consumed by man. It corrodes but preserves, desiccates but is wrested from the water."

|

| |

|

|

| Rock salt mining began here in 1923 by the Carey Salt Company. Today the mine measures about 2 1/2 miles north and south, and 1 1/2 miles east and west. As of July 2015, the mine had over 980 acres of useable space and more than 150 miles of tunnels. |

| |

|

|

|

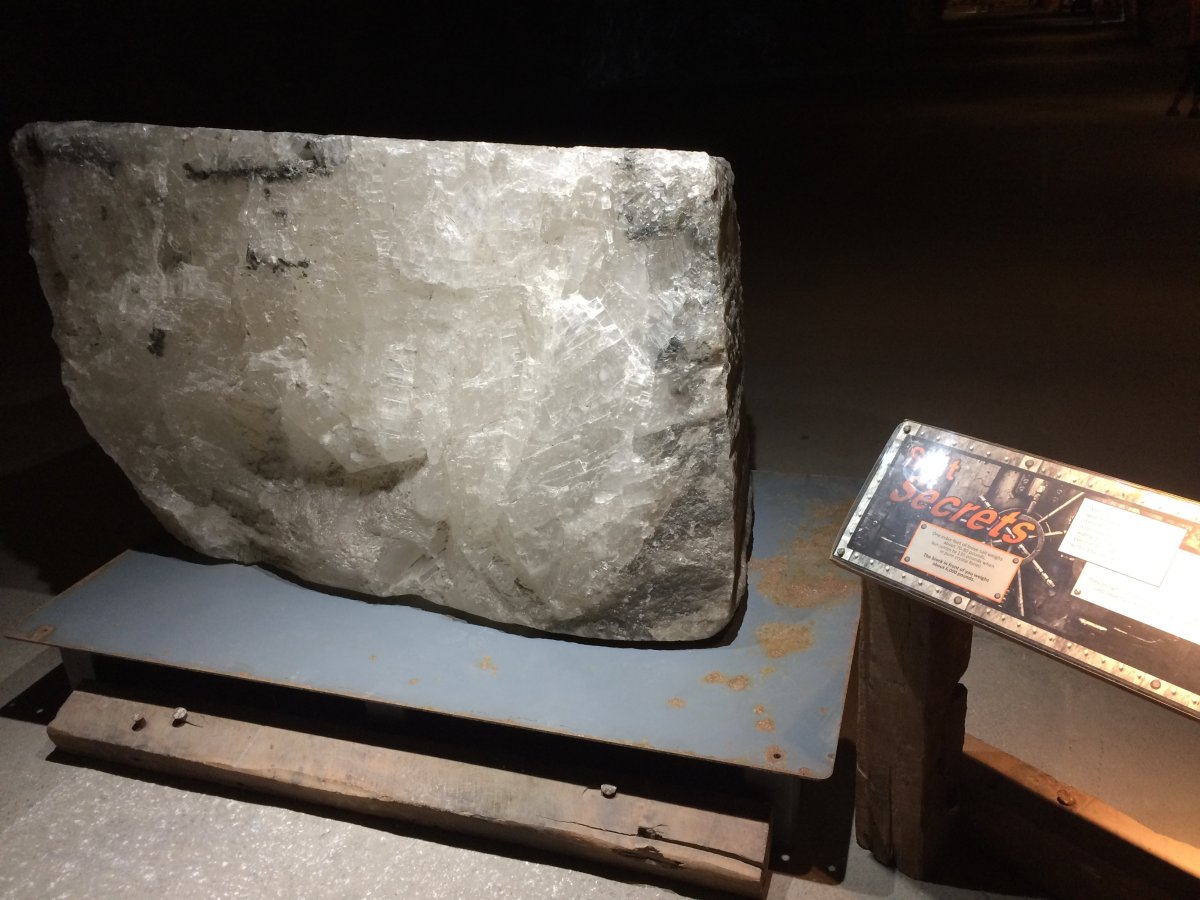

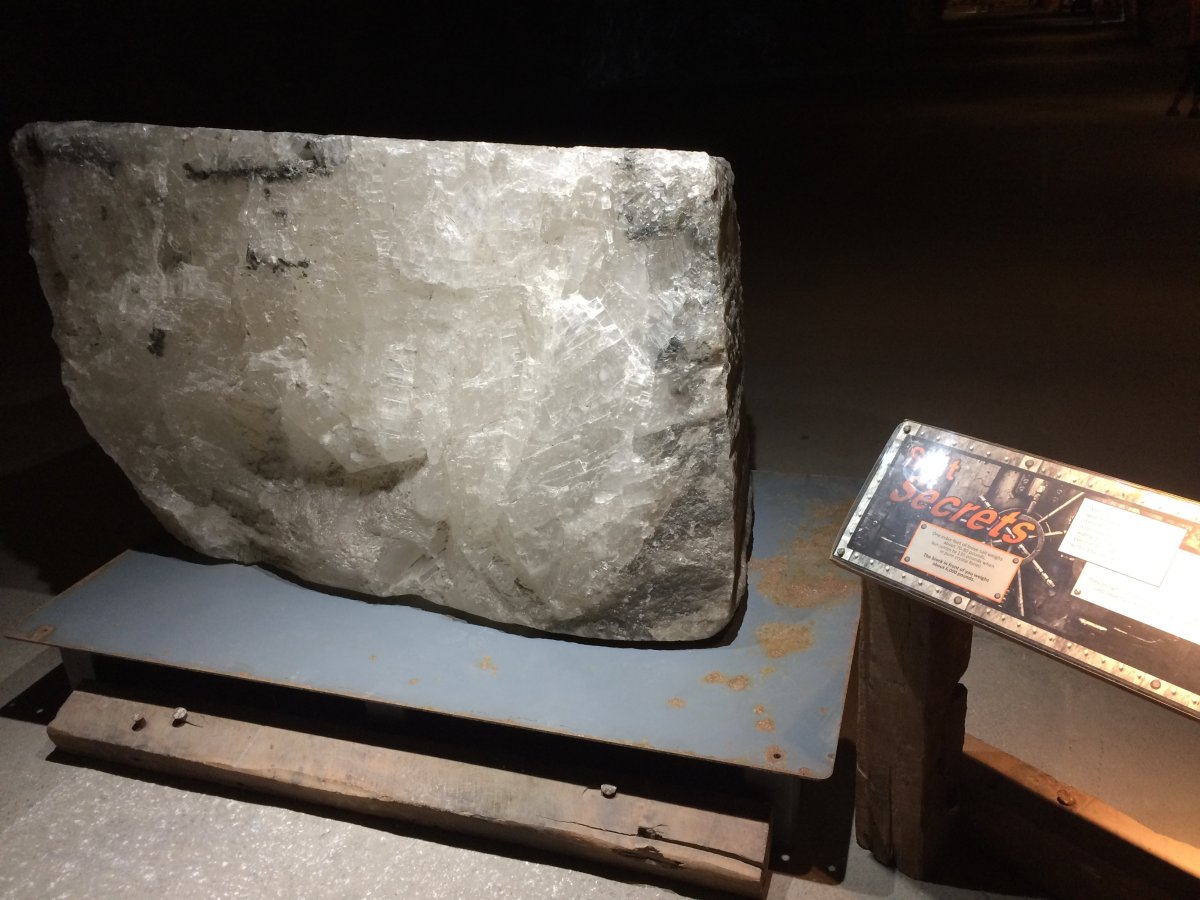

This is a huge block of salt and weighs 6,000 pounds.

Salt produced at the Hutchinson Salt Company is called rock salt, and about 500,000 tons is mined each year. It is principally used for industrial purposes and for de-icing highways. Their biggest customer is the city of Chicago.

When finely ground, the rock salt is also used for feeding livestock. It is not used for table salt or other purposes requiring a very pure type of salt.

|

| |

|

|

|

As you can see, the mine is huge. It's size reminded me of Mammoth Cave, although Mammoth was natural, and this was all man-made.

There is 300 feet of salt above and about 80 feet below. The salt is what's left of the old Permian Sea which existed 275 million years ago.

|

| |

|

|

|

A machine used to cut into the rock/salt wall. I remember seeing something like this over in the coal mine in England. The equipment and techniques used in coal and salt mines is pretty much the same. Equipment like this had to be disassembled so it could come down in the elevator, and then reassembled down here. The only thing that goes up in the elevator is people and product. When no longer used anymore, the equipment just stays down here.

This is a museum so it had information displays and video clips being played all over the place. We learned about all aspects of the modern-day mining process, as well as earlier procedures, through this three-part gallery. In the Undercut and drill area, the mine is set up for the first phase of a blast. An undercutter is used to cut a slot at the base of the rock, making it possible for the salt to drop. In this phase, a series of carefully sited holes are drilled into the salt wall. The next pillar of the Mining Gallery is the blast area, which illustrates how the room being mined is wired with explosives. On display is a powder car. It was formerly a drill, but was modified underground as a powder car and carried all the tools and materials needed to powder a room, including the explosives and wire. The third phase of the mining process featured is the Load Area. Miners used the Joy Loader on display from the 1940s until 1983 when the rail system was discontinued. Named for its manufacturer, the Joy Loader increased efficiency by eliminating the need to hand-load ore cars. This large piece of equipment, as so many others, was brought down the shaft in pieces and welded back together underground. Once a piece of equipment is underground, it remains. When equipment finally outlives its usefulness, it is usually abandoned in an area already mined. The shuttle featured in this gallery was also used from the 1940s until 1983 to take salt from the mine face to the loading station at the main rail line. Powered by a DC extension cord, the car reduced labor and increased efficiency because miners no longer had to lay rails to get the salt from the blast site to the main rail lines.

|

| |

|

|

| Yes, they had to disassemble this car to get it down, then re-assemble it. They only assembled the bare minimum required down here. |

| |

|

|

|

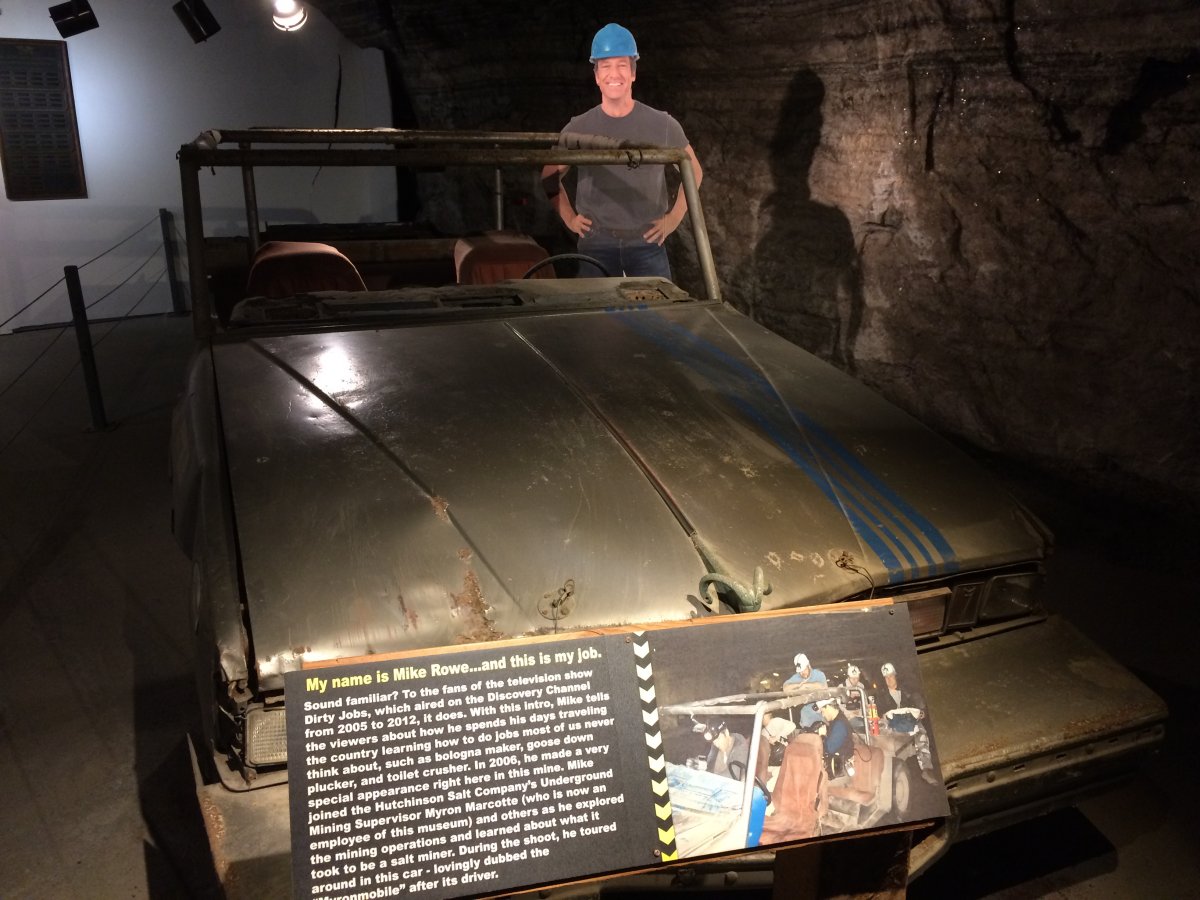

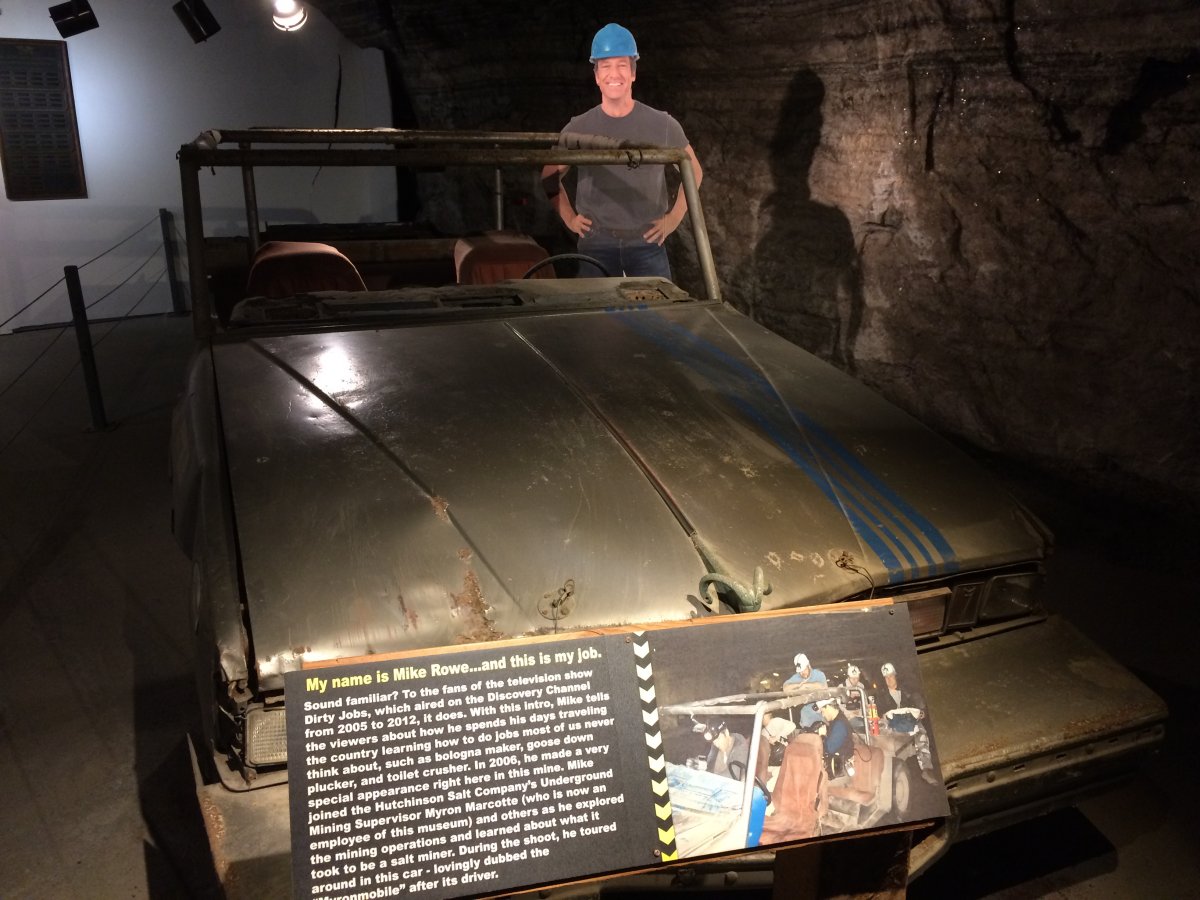

Yes, Mike Rowe, host of the Dirty Jobs TV show did an episode here.

|

| |

|

|

|

They use railways to transport product and people down here. I believe they are currently using conveyer belts to transport the product.

The conditions underground are very predictable and constant. The mine naturally maintains a temperature of 68 degrees with a relative humidity of around 45%.

We went on the underground tram tour, the "Dark Ride", that took us through a maze of chambers beyond the museum area to see various features of the mine environment – with a brief pause to experience the sensation of complete darkness.

|

| |

|

|

|

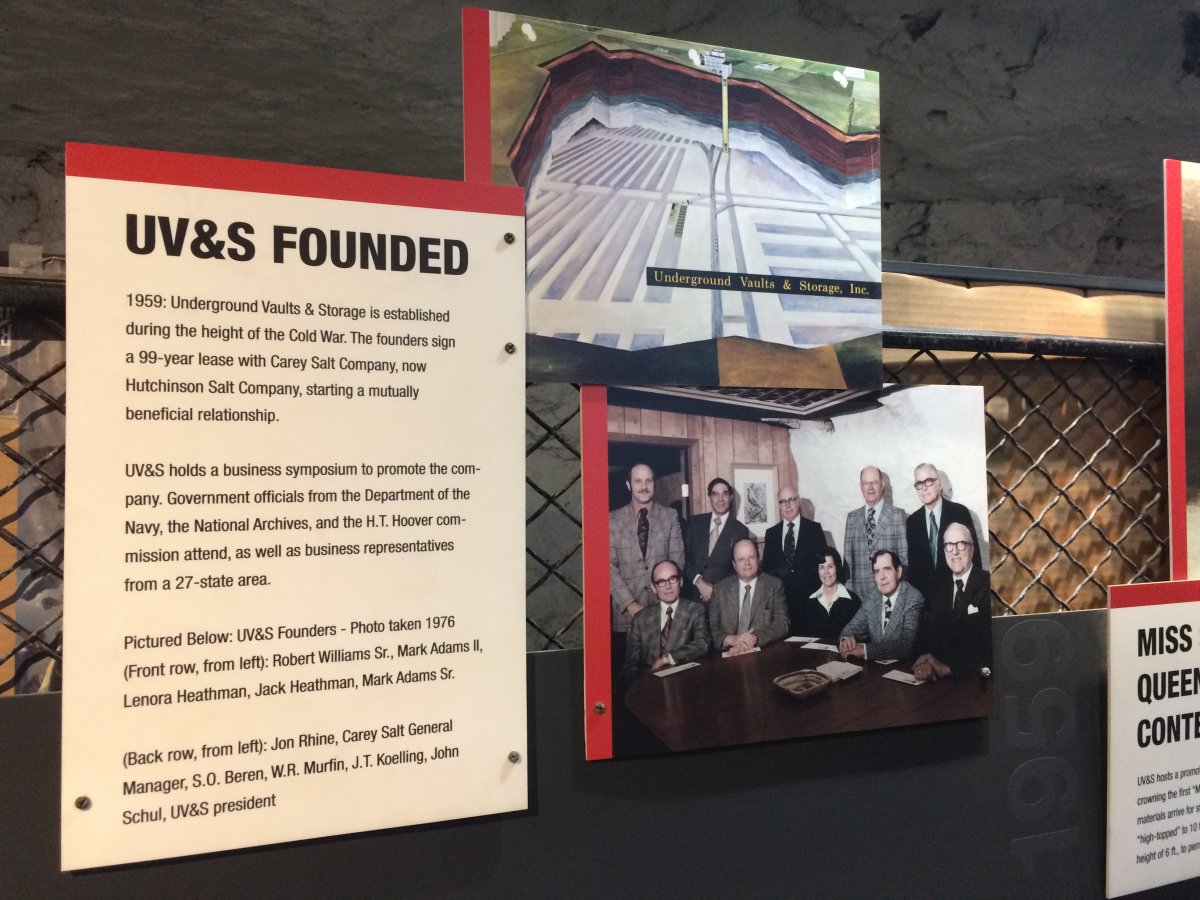

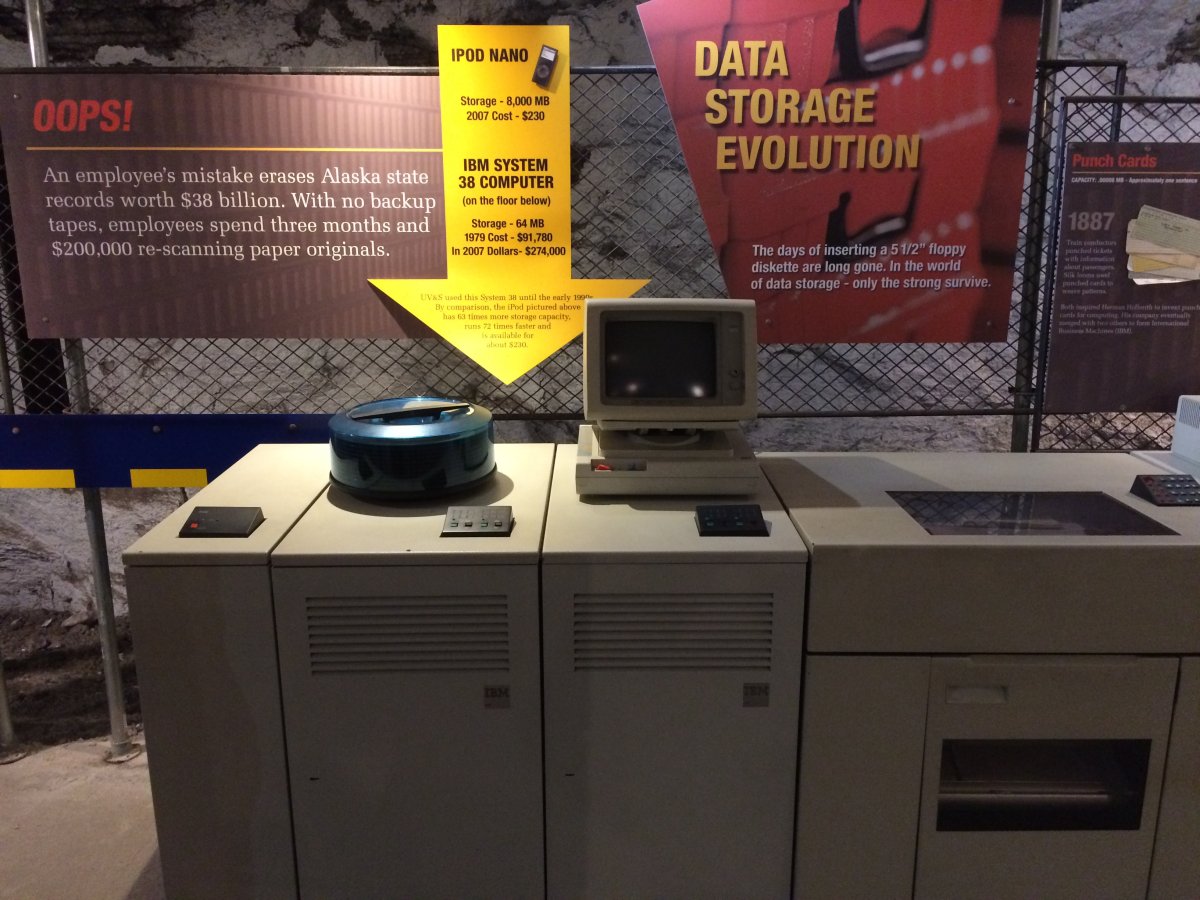

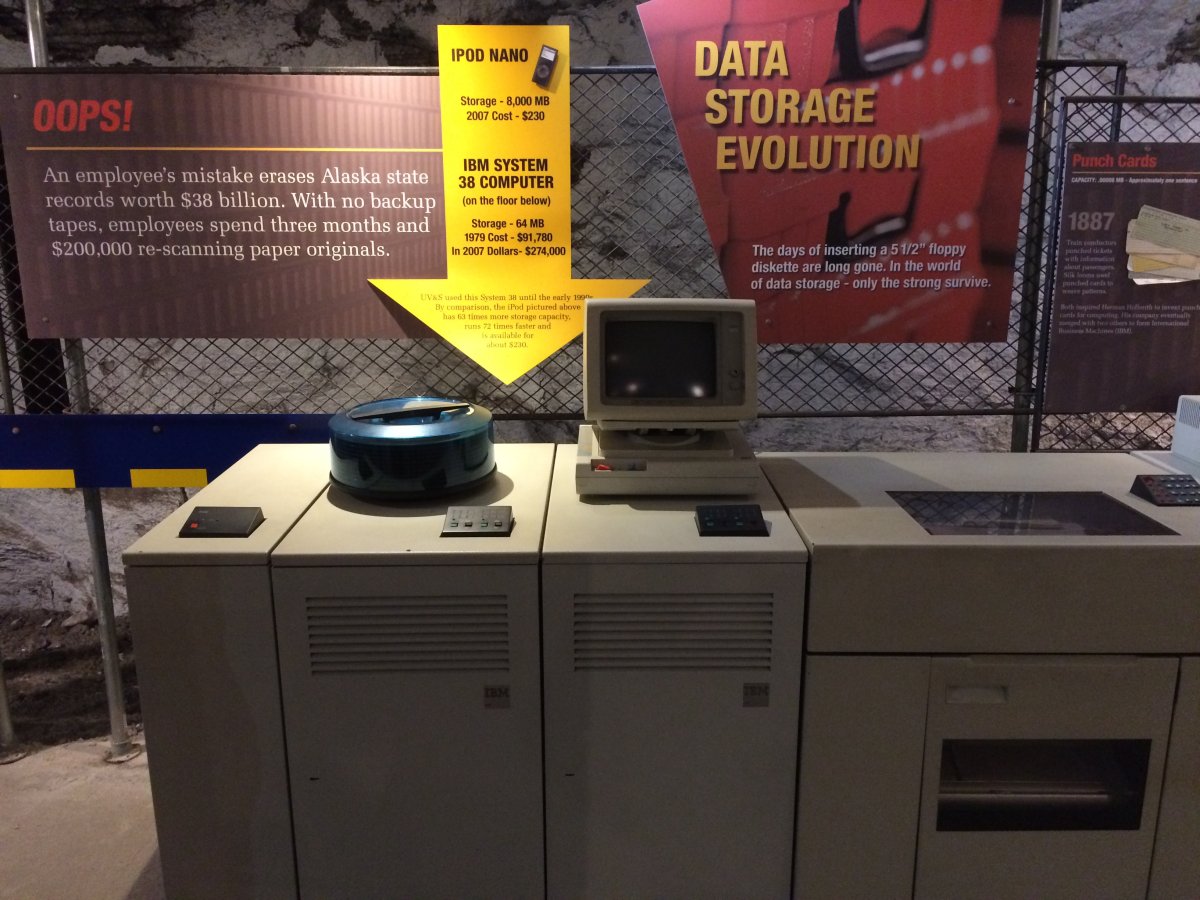

Another interesting thing about the salt mine is that it is used to store things. It makes sense: the temperature and relative humidity are constant, the security level created by “shaft only” access is high, and the underground things are safe from natural disasters like tornadoes, floods, hurricanes or earthquakes.

|

| |

|

|

| Some of the things stored here are the original camera negative of many movies, like Gone with the Wind and Ben Hur, as well as television show masters. UV&S also stores medical records, oil and gas charts, and a host of other valuable documents and other materials from all 50 states and many foreign countries. |

| |

|

|

|

This is a replica of the look and set-up of the storage facility.

|

| |

|

|

| Picking out a chunk of salt for a souvenir. |

| |

|

|

| Back on the surface. A pyramid of rock salt is in the distance, to be loaded onto railroad freight cars. |

| |

|

|

|

Sometimes GPS sends you on some sketchy roads. But it did get us to where we wanted to go.

|

| |

|

|

|

Leaving Hutchinson, we veared northwest and got back on Interestate 70. We stopped at Colby for the night: a highway town about 40 miles east of the Kansas/Colorado border state line.

Heading west through Kansas and the Great Plains.

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|